The Ground for Being Me

A child arrives not knowing they exist. They discover themselves in the mirror of their parents’ gaze—not through words, but through presence. Before language, before memory, before the machinery of self-concept begins its relentless construction, there is only this: Am I welcome here?

The answer to that question writes itself into the nervous system, into the felt sense of safety, into the very capacity to be present with what is. Acceptance is not a parenting technique. It is the ground from which a human being learns whether reality itself can be trusted.

What Acceptance Actually Is

We speak of acceptance as if it were a decision—something parents choose to extend or withhold. But genuine acceptance has nothing to do with approval. A parent can accept a child’s rage without approving of violence. They can accept a child’s fear without reinforcing avoidance, and they can accept a child’s peculiarities without pathologizing difference.

Acceptance is openness to what is actually here, right now, without the overlay of what should be. It’s the capacity to meet your child’s experience—their joy, their terror, their confusion, their aliveness—without needing to fix, improve, or redirect it toward something more manageable.

This is harder than it sounds. Because your child’s unfiltered experience will inevitably trigger your own unmetted territories. Their boundless enthusiasm confronts your learned restraint. Their raw need exposes your own unacknowledged hunger. Their authentic expression threatens the carefully constructed persona you’ve been maintaining since you, too, were a child learning which parts of yourself were welcome.

The Developmental Scaffolding of Self

Development doesn’t happen in a vacuum. A child doesn’t become themselves in isolation. They become themselves in relationship—through thousands of micro-interactions in which their experience is either met, deflected, reflected, or refracted.

When a toddler falls and looks to their parent, they’re not just seeking comfort. They’re asking: What just happened? How should I feel about this? Is this experience acceptable? The parent’s response—calm presence or anxious reaction, acknowledgment or dismissal—teaches the child how to relate to their own experience.

This process compounds. A child who learns that their sadness makes others uncomfortable begins to exile sadness from awareness. A child who discovers that their enthusiasm is “too much” learns to dampen their aliveness. A child who senses that their questions irritate their parents stops asking—stops wondering—stops being curious about the very reality they’re trying to understand.

The tragedy is not that children lose particular emotions or qualities. The tragedy is that they lose contact with their own interiority. They become oriented toward an external sense of okayness rather than an internal knowing of what’s true. The capacity for self-intimacy—the foundation of all genuine development—gets sacrificed to the need for conditional belonging.

The Hidden Mechanism of Conditional Acceptance

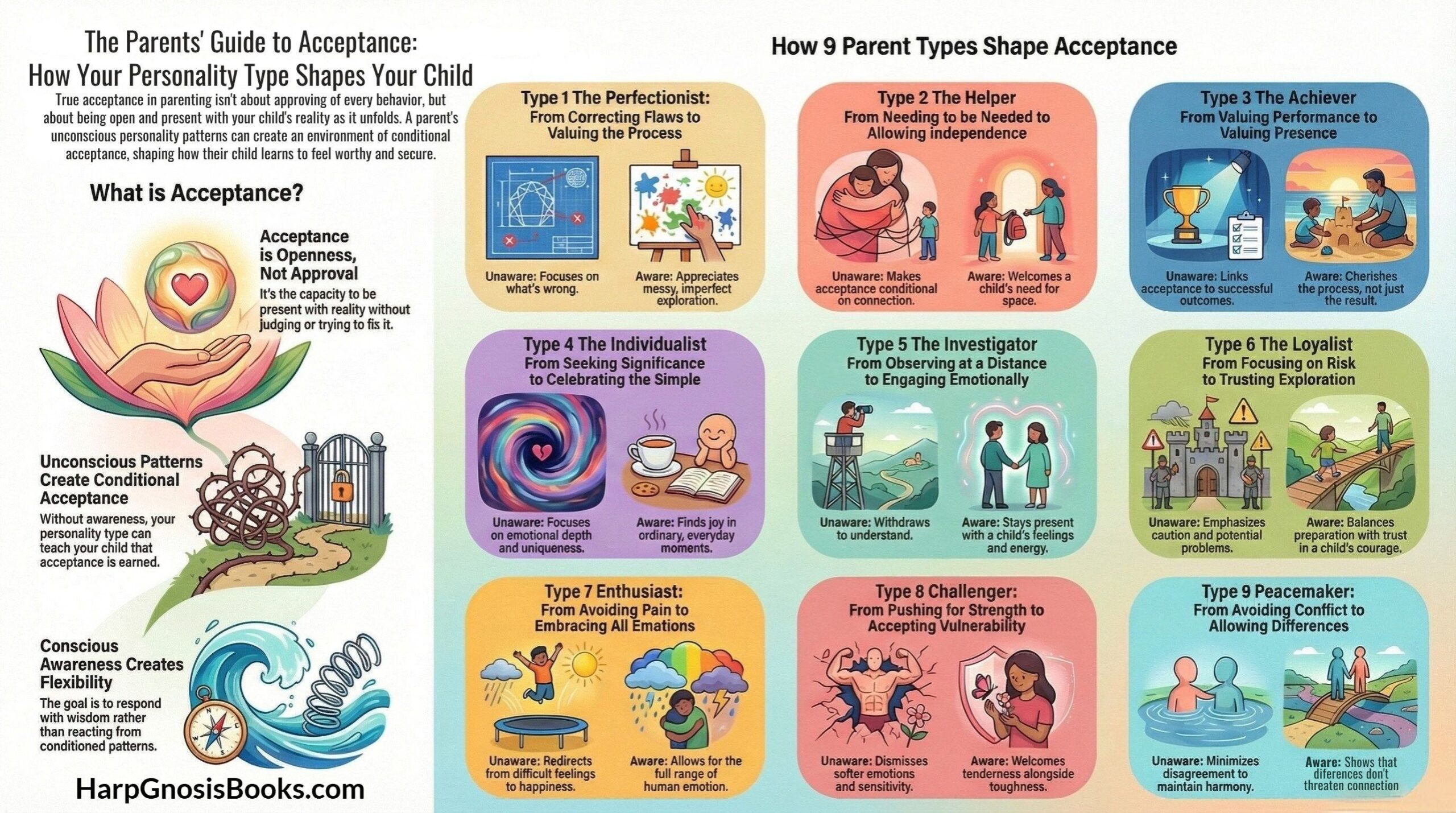

Most parents don’t set out to teach their children that love is conditional. But personality itself is a structure of conditionality. Each parent’s unconscious personality patterns create an invisible framework of what’s acceptable and what’s not.

The Type One parent, caught in their own perfectionism, focuses on what’s wrong—on the flaw in the drawing, the mistake in the math problem, the imperfection in behavior. The child learns: Process matters more than my presence. I am acceptable when I get it right.

The Type Two parent, needing to be needed, makes acceptance conditional on connection. Space becomes abandonment. Independence becomes betrayal. The child learns: I am acceptable when I prioritize others’ needs over my own.

The Type Three parent, valuing performance and outcome, teaches that acceptance follows achievement. Being is not enough; doing is what matters. The child learns: I am acceptable when I produce results, not when I simply exist.

Each type creates its own flavor of conditionality. And each child, exquisitely sensitive to the relational field, begins to shape themselves around these unspoken requirements.

What Gets Lost

When acceptance is conditional, children lose access to their essence—to the inherent okayness that exists before achievement, behavior, or performance. They lose the capacity to simply be without doing. They lose contact with their own experience in favor of monitoring how that experience lands on others.

This isn’t melodramatic. It’s mechanical. A nervous system that is chronically scanning for signs of acceptance or rejection cannot simultaneously be present in its immediate experience. The attention splits—the aliveness fragments. The child becomes an observer of themselves rather than an inhabitant of their own life.

And here’s the kicker: this pattern doesn’t end with childhood. It becomes the template for how we relate to ourselves for the rest of our lives. The internalized parent becomes the inner critic, the inner perfectionist, the inner evaluator who maintains the same conditional structure. We do to ourselves what was done to us—not because we’re broken, but because we learned that this is how being works.

The Practice of Unconditional Presence

True acceptance in parenting is not passive tolerance. It’s not indulgence. It’s not the absence of boundaries or guidance. It’s the capacity to be present with your child’s reality without needing it to be different for you to be okay.

This requires the parent to do their own work—to recognize where their personality creates blind spots, where their unconscious patterns demand that their child be a certain way to soothe the parent’s own unresolved anxiety, shame, or emptiness.

It requires the willingness to see your child as they actually are, not as you need them to be. To welcome their peculiar genius and their particular struggles. To trust that their essence—the quality of being that exists beneath behavior and performance—is inherently worthy of presence.

When a child experiences this kind of acceptance, something fundamental shifts. They learn that they can trust their own experience. That reality is not an enemy to be managed but a field to be explored, whose beingness is sufficient grounds for belonging.

This is the foundation. Not of self-esteem, but of self-intimacy. Not of confidence, but of presence. Not of success, but of aliveness.

Everything else in development builds on this ground.

John Harper is a Diamond Approach® teacher, Enneagram guide, and lifelong student of human development whose work bridges psychology, spirituality, and deep experiential inquiry. He is the author of Nurturing Essence: A Compass for Essential Parenting and The Enneagram World of the Child: Nurturing Resilience and Self-Compassion in Early Life, works that illuminate how essence shapes early psychological development. All titles are available on Amazon.